| Tour home |

| Preview |

| Photos |

| Live coverage |

| Start list |

| Stages & results |

| News |

| Map & profiles |

| Tour diaries |

| Features & tech |

| FAQ |

| Tour history |

Recently on Cyclingnews.com |

90th Tour de France - July 5-27, 2003

More book reviews |

Cyclingnews Tour de France book extract

"A chicken sandwich, a glass of beer and a 25-sprocket gear"

|

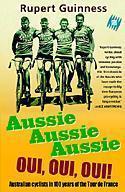

In Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, OUI, OUI, OUI! Australian cycling journalist Rupert Guinness tells the story of the Tour de France through the eyes of one of its most unlikely groups of riders, the men who trekked halfway round the world from Australia to race the roads of France. From Don Kirkham and Snowy Monroe in 1914 to the trio of Cooke, McEwen and O'Grady that dominates this year's points contest, Australians have made a mark on the Tour way beyond expectations of a country of just 19 million many thousands of kilometres from France.

Guinness uses the adventures, struggles and successes of the Australians to tell parts of the broader story of the Tour, as in this edited extract which looks at determined mid-seventies domestique Don Allan who rode two Tours before returning to the track.

Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, OUI, OUI, OUI! is available to buy online from Dymocks.

From Chapter 5: A tale of Two Tours

|

Don Allan stopped dead in his tracks on the sun-baked, sticky bitumen mountain road, high in the Alps bordering France and Italy. He could go no further on the fifteenth stage of the 1975 Tour de France. Standing, legs astride the top bar of his bike and torso slumped over his handlebars, he slowly looked up to the mountain summit and winced as he saw the hellish glow of blinding sunlight shrouding the crowd-covered peak. It was as if he were pleading for mercy, for the pain to end there and then. Allan was only a few kilometres from the top and another long cooling descent to the foot of another climb. But he may as well have been at the bottom of this twisting mountain where his torture had begun. He had made so little advance on the nearest stragglers, let alone leaders, that Allan thought he might as well not be on the Tour. He shook his head and dismounted.

After spending most of the previous stages in the mountains riding off the back of the race, Allan's mind was too dizzy from the effort to know where he was placed on the stage. Even today, he still can't say where he was. When asked, he replies that it was somewhere on one of four mountains that lie between the city of Nice on the French Riviera and the ski station summit of Pra Loup (1630 m) where the 217 km stage finished. What he did know was that he was once more alone, in his now daily struggle to make the finish within the allocated time limit and avoid elimination by the race organisers.

|

“ When you get to the mountains it feels like you've ridden one-and-half races already. ” |

Allan soft-pedalled to the side of the road, prised himself off the saddle, and then threatened the Dutch driver of the car behind him that he would have no further part of the Tour - unless he could get a chicken sandwich, a glass of beer and a 25-sprocket gear for his rear wheel to make climbing the mountains ahead more possible, if not easier. All these items are supposedly unattainable in the mountain wilderness; it was as if Allan was taking hostage of his fate and, hoping the ransom would not be delivered, be forced to carry out his threat. 'I just spat the dummy and was naming something they couldn't come up with. They all started laughing,' recalls Allan, adding that he didn't see the humour. 'The team director said, "Where am I going to get that?" and toddled off. Then the mechanic said, "I haven't got a 25 [sprocket] but a 24", so I said, "That'll do." They didn't make a 25. Then the director came back with a chicken sandwich and an old French lady in a black coat had a glass of wine for me. So I got on [my bike] again. I wasn't really going to give up. I was just being cantankerous.'

[Despite this dummy-spit, Don Allan was having a much better time of the 1975 Tour than he had the previous year. Like many talented but not first-rank riders, the mountains were his nemesis...]

Allan says that even before he felt the first incline of a mountain under his lightweight wheels, he knew the only way up would be agonisingly slow: 'I was quite a good climber in Australia. But the Tour is so hard. A bloke may be half a centimetre per hour quicker than you, but you just can't get on [his wheel]. It gets to another limit. You are right on the edge and you can't do much about it. I just suffered and knew I was going to go out the back and ride my own tempo.'

In the two Tours he rode, Allan was the sole Australian and one of only two English-speaking riders in the race. Both tours were historic. The first in 1974 ended with the final and record-equalling fifth career victory by Eddy Merckx - a.k.a 'the Cannibal' because of his ferocious appetite for winning every race. Allan's second Tour in 1975 marked the start of Merckx's downfall when Frenchman Bernard Thévenet - who would later become friends with Allan as well as the darling of France - won for the first of two times.

1974: Matching up with Merckx

When the 1974 Tour started its 4098 km clockwise excursion around France in Brest, a fishing port on the west coast of Brittany, Merckx, then twenty-eight, and Allan, then twenty-four, were poles apart in their expectations. Merckx was aiming to join Frenchman Jacques Anquetil as one of only two riders who had won five Tours. Allan's objective, besides finishing the Tour in Paris after its twenty-two stages, was to help his Dutch team and its leader, neo-pro Fedor Den Hertog, place highly in the overall classification.

In the first week of the Tour it is not surprising that the overall favourites for the yellow jersey are often racked with nerves, fearing they may crash or lose vital time as less credentialed riders - or the sprinters who will take a back step in the mountains - vie for any winning chance that arises. Risks are plentiful in the speeding pack, with riders darting and weaving within centimetres of one another for gaps that don't seem to exist. With only the slightest touch of wheels, a pack of riders can fall like dominoes, putting an end to any rider's Tour in a second.

For Allan and the Frisol team, the first week of the 1974 Tour was a case in point. After celebrating a win on stage two by Dutch teammate Henk Poppe at Plymouth, England, Frisol backed up after the Channel voyage to France and stage three from Morlaix to St Malo by losing Dutch champion Cees Priem in a spectacular crash on the finish line. In a mad, high-speed dash down the left-hand side of the barriers, Priem took down several other riders with him - including another Frisol teammate, Dutchman Piet Van Katwijk, who needed stitches to his head. Although he gained ninth place, Priem suffered a hairline fracture to the pelvis, and was unable to start the next day's stage to Caen.

After several days of battling the sprinters and a victory by his team in the team time trial, Merckx took outright ownership of the yellow jersey on stage seven, the 221.5 km leg from Mons through the forested Belgian Ardennes to Châlons-sur-Marne. From there to the finish he did not relinquish cycling's most prized garment, despite being bravely pursued by Poulidor. His seventh stage win was later labelled opportunistic, for Merckx reportedly jumped from the pack at a corner on the finishing circuit and into the slipstream of a television motorbike. The slipstream gave him the gap he needed to win.

That day, Allan claimed his best place for the week (fourteenth) after helping set up his sixth-placed Dutch teammate Van Katwijk for the sprint finish. But with the Alps approaching and another two weeks to go, he knew the Tour had only begun, even if his exhausting role as a domestique told him it should almost be over. 'It is hard when you are a domestique. You do your job properly, like getting the bidons, the raincoats ... When you get to the mountains [it feels like] you've ridden one-and-half races already,' he said.

Allan was not alone in expressing the rigours endured by domestiques - of which Australian riders are reputably some of the best. Their feats may often go unnoticed as all the praise is aimed at the winner who stands on the podium, spraying the crowd with champagne. But inside any team, the domestique is recognised as a vital element to winning a race. Even the mercurial Eddy Merckx needed them.

As the Tour edged towards the Alps, Allan was pleasantly reminded of the esteem in which domestiques are held by his team directeur-sportif, Piet Liebregts. Liebregts felt that workers like Allan deserved more public recognition for their efforts. He was especially angry about the lack of kudos they received compared to soccer players who, Liebregts felt, had it all too easy. According to Allan, 'Piet said he would love to get them to follow the Tour for a couple of days; not the leading riders, but the last few and then they would learn what suffering was about.'

Once the Alps arrived, Allan also learned a thing or two about suffering. The three days spent ascending and descending their peaks were action-packed. It was in the Alps that the real battle for the yellow jersey began, and so too for Allan the battle to survive and make it to Paris.

From the moment the start-flag dropped, attacks began in the first stage in the mountains - a 241 km run from Besançon to Aspro Gaillard. The Spaniards launched their first assault on Merckx, and Poulidor also dealt his first cards. But Merckx and his Molteni henchmen were onto every move on a stage that included five climbs of varying lengths and grades, the first coming after only 5 km. After a brutally fast stage Merckx took the finishing sprint.

Merckx's victory at Aspro Gaillard ensured he kept the yellow jersey. But of more significance to a long-discarded and rapidly tiring Allan, Merckx's sprint set the clock running for him to finish within the time limit. As the field finished in groups of ones, twos and threes, Allan and Frisol teammates, Van Katwijk and Poppe, reached the finish 43 minutes down on Merckx. Their reward was to endure it all again the next day.

Allan rued such an early fast pace in the mountains. The option of quitting was always open to him. Four riders left the race that day. Allan admits the idea always became tempting when he saw riders abandon.

But quitting the Tour is certainly not a ceremony of pomp and pageantry. The rider first slows to a halt, dismounts and often slowly straightens his aching back. Then, after pausing for a final moment of solitary reflection (or second doubt), he nods to an attending race commissaire (judge) to signal that, yes, he may now unpin his race number. Once made, this decision cannot be reversed. It is simple and swift, with few words spoken. More often than not, it is an act of surrender that leaves the rider in tears in front of a swarm of photographers trying to capture the moment. The day after, some riders feel guilt and shame, an experience Allan says he wanted no part of: 'I spent a lot of time on my own in the mountains. You see them giving up but you think that is the easy way out. I am a fighter. I don't like giving up.'

Also pushing Allan was his desire to join the shortlist of Australians who have finished the Tour. Up until 1974, only six Australians from the eleven starters had finished in Paris: Don Kirkham (1914), Iddo 'Snowy' Munro (1914), Sir Hubert Opperman (1928, 1931), Percy Osborne (1928), Richard 'Fatty' Lamb (1931) and Russell Mockridge (1955). Allan wanted his name among them. But for that to happen he knew he had to hang on through the Alps, a task that was made harder by the aggressive assault on Merckx's race lead by Poulidor and the Spanish riders.

The rest day couldn't come sooner for Allan - or anyone for that matter - after Merckx won the relatively short 131 km tenth stage from Aspro Gaillard to Aix-les-Bains.

After the rest day, Allan struggled through the eleventh stage, a 199 km run from Aix-les-Bains to Serre-Chevalier which Merckx began with a 2 minute 1 second overall lead on Poulidor. It was a brutal leg that saw seven riders quit the Tour, leaving it with 115 riders. Among those who abandoned was the 1973 runner-up, and the next year's winner, Thévenet, who had fallen ill overnight. To the dismay of the French, he was forced to stop on the slopes of the Col du Télégraphe just as the aggression began to take shape. Allan came home third-last.

But the Col du Télégraphe was only a precursor to what lay ahead - the more demanding rise up the summit of the Col du Galibier (2556 m) which began 5 km after the Télégraphe summit where the first serious group escaped. But it was an attack by Frenchman, Roger Pingeon, and Lopez-Carril with 10 km to go on the Galibier that really set the stage alight. The move forced Merckx to lead the chase - an effort that left Poulidor floundering under the pace.

The last 5 km of the Galibier unleashed carnage on the front-runners who were now a threesome of Merckx, Lopez-Carril and Aja. Lopez-Carril again attacked and was first over the summit. Behind him came Merckx with Aja and another Spaniard from the Kas team, Francisco Galdos, in tow. In their wake was a string of riders leading all the way back to Allan.

With a Spaniard in front and two more in tow, Merckx again had no choice but to lead the chase of Lopez-Carril down the winding Galibier descent and then along the valley for the 20 km stretch to the ski resort town of Serre-Chevalier. Lopez-Carril still won, but Merckx - trying to minimise the time loss - rode as hard as he could to the finish and managed to win the three-up sprint for second place. Then came an exhausted line of riders. One was Poulidor who finished tenth at 6 minutes 17 seconds to Lopez-Carril and 5 minutes 23 seconds behind Merckx. After starting the stage second overall at 2 minutes 1 second to Merckx, the shattered Frenchman was now sixth and 7 minutes 24 seconds down overall. Closest on Merckx's tail were the Spaniards, Aja at 2 minutes 20 seconds, and Lopez-Carril at 2 minutes 34 seconds. Allan customarily finished at the tail-end, third-last at more than 30 minutes.

Leaving the Alps brought no respite. The Tour's entry into the steamy and sweltering region of Provence only heralded more pain. Highlighting the 231 km twelfth stage from Savines-le-Lac to Orange was the feared ascent up the scree-sloped rise of Mont Ventoux, one of the Tour's most fabled climbs and known as the 'Giant of Provence'. Mont Ventoux can be ascended from two directions: from the north and the south. Either way is a brutal challenge, and unsurprisingly, it was not until the race reached the 21.1 km climb that the stage saw any serious action. On this occasion, the field tackled the climb to its 1912 m summit from the south. The long, winding route began with the bunch being protected from the burning sun by the shade of pine trees that blanket the first 15 km of the climb. But cruelly, just as the route turns left and upwards at le Chalet-Reynard, the line of cooling shadows abates as the road leads into a vast furnace of heat, blue skies and testing Mistral headwinds, opening the riders to the hellish view of the barren, moon-like scree slopes.

For Allan and the Frisol team, it was a day of resounding success as the team very nearly celebrated their second win. For in second place - outsprinted by Spruyt - was their team leader, Den Hertog, finally using his power and strength wisely. With Spruyt already away, it was Den Hertog who ignited the main chase of Spruyt and four others, his effort even catching Merckx off-guard. In the finish at Orange, Spruyt - who had done little work in the bunch - won, but only with half a wheel to spare. Allan struggled to the finish, but at least he did so with more company than usual. He finished in a group of eighteen riders at 10 minutes 44 seconds to Belgian stage winner Jozef Spruyt, one of Merckx's teammates.

Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, OUI, OUI, OUI! is published by Random

House, RRP: $27.95.

Australian readers can purchase

copies online from Dymocks.

|